Alexander Protopopov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

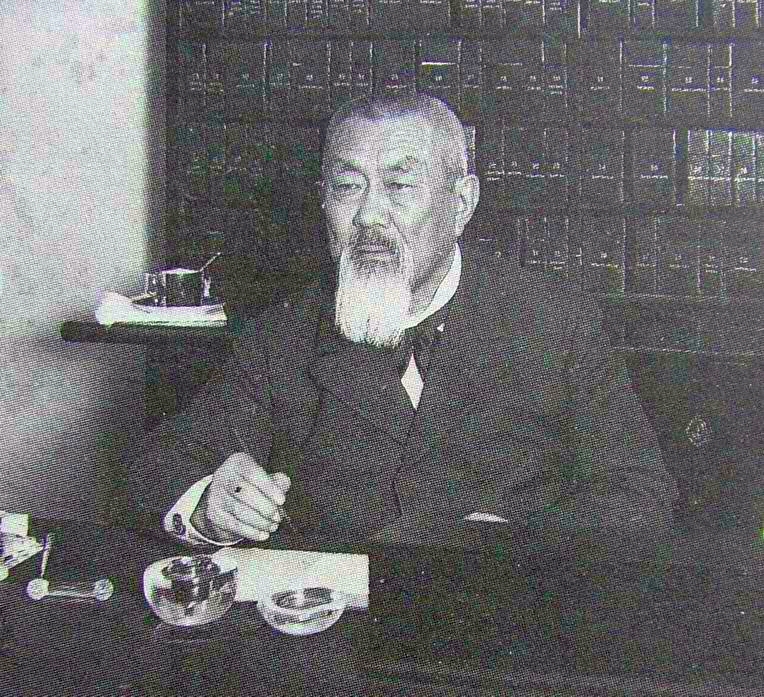

Alexander Dmitrievich Protopopov (; 18 December 1866 – 27 October 1918) was a

On 20 July 1916, Protopopov formally met with Tsar

On 20 July 1916, Protopopov formally met with Tsar

The fall of the tsarist regime. Volume 2 / Interrogation of A.D. Protopopov on April 21, 1917

/ref>

Features And Figures Of The Past. Government And Opinion In The Reign Of Nicholas II.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Protopopov, Alexander 1866 births 1918 deaths Octobrists Marshals of nobility Members of the 3rd State Duma of the Russian Empire Victims of Red Terror in Soviet Russia People from Ulyanovsk People from Ulyanovsk Oblast Russian nobility Members of the 4th State Duma of the Russian Empire Executed Russian people

Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

publicist and politician who served as Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

from September 1916 to February 1917.

Protopopov became a leading liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

politician in Russia after the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

and elected to the State Duma

The State Duma (russian: Госуда́рственная ду́ма, r=Gosudárstvennaja dúma), commonly abbreviated in Russian as Gosduma ( rus, Госду́ма), is the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia, while the upper house ...

with the Octobrist Party

The Union of 17 October (russian: Союз 17 Октября, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: Октябристы, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in ...

. Protopopov was appointed Minister of the Interior with the support of Empress Alexandra during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, but his inexperience and mental instability failed to relieve the effects of the war on Russia and contributed to the decline of the Imperial government. Protopopov remained Minister of the Interior despite attempts to remove him for his policy failures, worsening mental state, and close relationship with Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (; rus, links=no, Григорий Ефимович Распутин ; – ) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Nicholas II, the last Emperor of Russia, thus g ...

until he was forced to resign shortly before the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

.

According to Bernard Pares

Sir Bernard Pares KBE (1 March 1867 – 17 April 1949) was an English historian and diplomat. During the First World War, he was seconded to the Foreign Ministry in Petrograd, Russia, where he reported political events back to London, and worke ...

, Protopopov "was merely a political agent; but his intentions as to policy, considering the post which he held, are of historical interest."

Early life

Alexander Dmitrievich Protopopov was born on 18 December 1866 inSimbirsk

Ulyanovsk, known until 1924 as Simbirsk, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Ulyanovsk Oblast, Russia, located on the Volga River east of Moscow. Population:

The city, founded as Simbirsk (), w ...

(the home of both Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; Reforms of Russian orthography, original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months ...

and Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

), the son of a wealthy member of the local nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

who owned extensive land holdings and a textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

factory. Protopopov attended the select as a cadet

A cadet is an officer trainee or candidate. The term is frequently used to refer to those training to become an officer in the military, often a person who is a junior trainee. Its meaning may vary between countries which can include youths in ...

before being commissioned into the Horse Grenadier Regiment of the Imperial Guard

An imperial guard or palace guard is a special group of troops (or a member thereof) of an empire, typically closely associated directly with the Emperor or Empress. Usually these troops embody a more elite status than other imperial forces, in ...

. After leaving the army in 1889, Protopopov studied law and became a director of his father's textile factory. At some point, Protopopov moved to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

where he became active in the financial community.

Political career

Protopopov was elected in 1907 as a member of the centralistOctobrist Party

The Union of 17 October (russian: Союз 17 Октября, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: Октябристы, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in ...

as a delegate to both the Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

and Fourth Duma

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the Governing Senate in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four times ...

s. In 1912, Protopopov was elected Marshal of Nobility of Karsunsky Uyezd Karsunsky Uyezd (''Карсунский уезд'') was one of the subdivisions of the Simbirsk Governorate of the Russian Empire. It was situated in the western part of the governorate. Its administrative centre was Karsun.

Demographics

At the t ...

. In 1916, was elected as Marshal of Simbirsk Governorate

Simbirsk Governorate (russian: link=no, Симбирская губерния, ''Simbirskaya guberniya'') was an administrative division (a '' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire and the Russian SFSR, which existed from 1796 to 1928. Its administra ...

and also became president of the Council of the Metal-Working Industry, controlled by banks dependent on German syndicates.

In November 1913 or May 1914, Protopopov was appointed as vice-president of the Imperial Duma

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the Governing Senate in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four times ...

under Mikhail Rodzianko

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko (russian: Михаи́л Влади́мирович Родзя́нко; uk, Михайло Володимирович Родзянко; 21 February 1859, Yekaterinoslav Governorate – 24 January 1924, Beod ...

, serving as Deputy Speaker from 1914 to 1916. Protopopov founded a newspaper ''Russkaya Volya'' ("The Will of Russia") which was financed by the banks and appointed Nikolay Gredeskul

Nikolay Andreyevich Gredeskul (Russian: Николай Андреевич Гредескул; 20 April 1865 – 8 September 1941) was a Russians, Russian liberalism, liberal politician.

Biography Origins

He was from an old noble family of Moldavi ...

and Alexander Amfiteatrov

Alexander Valentinovich Amfiteatrov (Amphiteatrof) (russian: Алекса́ндр Валенти́нович Амфитеа́тров); (December 26, 1862 – February 26, 1938) was a Russian writer, novelist, and historian.

Biography

Born a prie ...

as journalists. According to Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Protopopov was hospitalized from the end of 1915 for six full months in the clinic of Peter Badmayev. In Spring 1916, at the request of Rodzianko, Protopopov led a delegation of Duma members with Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, p=mʲɪlʲʊˈkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Con ...

to strengthen the ties with the Entente powers

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

, Russia's western allies in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Protopopov met with the German industrialist and politician Hugo Stinnes

Hugo Dieter Stinnes (12 February 1870 – 10 April 1924) was a German industrialist and politician. During the late era of the German Empire and early Weimar Republic, he was considered to be one of the most influential entrepreneurs in Europe.

...

, the banker Fritz M. Warburg, and the Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

Minister of Foreign Affairs Knut Wallenberg. Protopopov faced a violently hostile reception from the pro-British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

Russian liberals upon his return from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and the United Kingdom, and in self-defence alleged that Warburg had initiated the talks. Protopopov's secret contacts on peace and a swap between Russia and Germany became a scandal, which according to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' was an indication of the rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word ''rapprocher'' ("to bring together"), is a re-establishment of cordial relations between two countries. This may be done due to a mutual enemy, as was the case with Germ ...

between the Russian and German Governments. Protopopov was widely suspected of contacts with German diplomat Hellmuth Lucius von Stoedten. In 1925, the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

journalist Theodor Fritsch

Theodor Fritsch (born Emil Theodor Fritsche; 28 October 1852 – 8 September 1933), was a German publisher and journalist. His antisemitic writings did much to influence popular German opinion against Jews in the late 19th and early 20th c ...

rewrote the story, alleging Warburg had wrecked Imperial Germany, advanced the Communist cause, and changed the entire course of European history.)

Minister of Interior

On 20 July 1916, Protopopov formally met with Tsar

On 20 July 1916, Protopopov formally met with Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

who described him as "a man I like very much". Alexander Kerensky had described him as "handsome, elegant, captivating .... moderately liberal and always pleasant". Repeatedly, Empress Alexandra urged her husband to appoint Protopopov as Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

as placing the vice-president of the Duma in a key post might improve the relations between the Duma and the monarchy. Although impressed by Protopopov's charm, Nicholas was initially doubtful about his suitability for a position that included responsibility for police and food supplies at a time of instability and shortages. Protopopov had no bureaucratic

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

experience and knew little of the police department. However, the Tsar approved his appointment as manager of the Ministry of Interior some time between 16 and 20 September 1916. According to Richard Pipes, Protopopov received carte blanche

A blank cheque in the literal sense is a cheque that has no monetary value written in, but is already signed. In the figurative sense, it is used to describe a situation in which an agreement has been made that is open-ended or vague, and therefo ...

to run the country. Although earlier considered fairly liberal, Protopopov saw his new role as that of preserving Tsarist autocracy

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except perh ...

. With the Tsar absent at the Stavka

The ''Stavka'' (Russian and Ukrainian: Ставка) is a name of the high command of the armed forces formerly in the Russian Empire, Soviet Union and currently in Ukraine.

In Imperial Russia ''Stavka'' referred to the administrative staff, a ...

headquarters, the government of Russia appeared managed as a kind of personal concern between the Empress, Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (; rus, links=no, Григорий Ефимович Распутин ; – ) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Nicholas II, the last Emperor of Russia, thus g ...

and Protopopov, with the auxiliary assistance of Anna Vyrubova

Anna Alexandrovna Vyrubova (''née'' Taneyeva; russian: А́нна Алекса́ндровна Вы́рубова (Тане́ева)); 16 July 1884 – 20 July 1964) was a Russian Empire lady-in-waiting, the best friend and confidante of Tsarin ...

. Protopopov continued the reactionary policies of his predecessor, Boris Stürmer

Baron Boris Vladimirovich Shturmer (russian: Бори́с Влади́мирович Штю́рмер) (27 July 1848 – 9 September 1917) was a Russian lawyer, a Master of Ceremonies at the Russian Court, and a district governor. He became a ...

, with support from the Empress.

According to Rodzianko and Bernard Pares

Sir Bernard Pares KBE (1 March 1867 – 17 April 1949) was an English historian and diplomat. During the First World War, he was seconded to the Foreign Ministry in Petrograd, Russia, where he reported political events back to London, and worke ...

, by this point Protopopov was mentally unstable and his speeches were incohesive. "In spite of his planning on paper, he seems never to have had any effective proposal for the solution of any of the grave and critical problems which he was there to settle." In October, Protopopov proposed to let a group of Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

bankers purchase all the Russian bread and distribute it through the country. Protopopov ordered the release of Vladimir Sukhomlinov

Vladimir Aleksandrovich Sukhomlinov ( rus, Владимир Александрович Сухомлинов, p=sʊxɐˈmlʲinəf; – 2 February 1926) was a Russian general of the Imperial Russian Army who served as the Chief of the General Staf ...

, the former Minister of War who was arrested in a high-profile scandal regarding allegations of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and abuse of power

Abuse is the improper usage or treatment of a thing, often to unfairly or improperly gain benefit. Abuse can come in many forms, such as: physical or verbal maltreatment, injury, assault, violation, rape, unjust practices, crimes, or other t ...

, and accused responsibility for Russia's numerous early defeats in World War I. When the Russian public learned Protopopov had visited the now-destitute

Extreme poverty, deep poverty, abject poverty, absolute poverty, destitution, or penury, is the most severe type of poverty, defined by the United Nations (UN) as "a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, includi ...

and despised Sukhomlinov at his apartment, he was heavily criticized in the Duma and damaged the reputation of the government. Protopopov intended to suppress public organizations, especially Zemgor Zemgor (russian: Земгор or Объединённый комитет Земского союза и Союза городов; literally ''United Committee of the Union of Zemstvos and the Union of Towns'') was a Russian organization created in ...

and the War Industry Committees, to win back the support of the business world, which he knew better than anything else. In November, Protopopov sought the dissolution of the Duma.

Alexander Trepov

Alexander Fyodorovich Trepov (; 30 September 1862, Kiev – 10 November 1928, Nice) was the Prime Minister of the Russian Empire from 23 November 1916 until 9 January 1917. He was conservative, a monarchist, a member of the Russian Assembly, a ...

, the new prime minister, informed Protopopov that he wished him to give up his post in the Ministry of the Interior and take over that of Commerce, but Protopopov refused. In November 1916, Trepov made the dismissal of Protopopov an indispensable condition of his accepting the presidency of the Council. The Empress, who disliked Trepov, tried to retain Protopopov in his influential position in the Ministry of the Interior. On 14 November 1916 ( O.S.), Trepov travelled to the Stavka to meet with the Tsar to discuss the growing crisis caused by World War I, but threatened to resign on the next day. On 17 November, Nikolai Pokrovsky was appointed as a foreign minister, but announced his resignation four times over disagreements with Protopopov. Pokrovsky favored the attraction of the American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

financial capital into the Russian economy. On 7 December, the cabinet demanded that Protopopov should go to the Tsar and resign, but he was instead appointed as Minister at the request of the Tsarina. In December 1916, Protopopov banned the zemstvos

A ''zemstvo'' ( rus, земство, p=ˈzʲɛmstvə, plural ''zemstva'' – rus, земства) was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexand ...

from meeting without police agents in attendance. "Protopopov felt that this organization was dominated by a revolutionary salaried staff and that in general the demand of opposition activists for a role in food-supply matters was meant to further political, and not practical, aims." When the supply problems proved beyond Protopopov's capabilities to manage, he lifted registration requirements on Jewish residents of Moscow and other cities. Early 1917 Protopopov, who excused himself many times and did not attend the meetings of the government; he suggested dissolution or postponing the Duma even further. On 8 February, at the wish of the Tsar, Nikolay Maklakov

Nikolay Alexeyevich Maklakov (9 September 1871 – 5 September 1918) (N.S.) was a Chamberlain of the Imperial court, a Russian monarchist, and a prominent right-wing statesman. He was a governor in the Ukrain and state councillor who served as ...

, together with Protopopov ..., drafted the text of the manifesto on the dissolution of the Duma. On , the Duma was dissolved and Protopopov was proclaimed dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

.

Relations with Rasputin

Grigori Rasputin had a closer relationship with Protopopov than with his predecessor Stürmer, and had known each other since 1912. Protopopov was suffering from the effects of advancedsyphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

which made him physically weak and mentally unstable, and resulted in a mystical and deeply superstitious condition. Protopopov was a frequent visitor to Peter Badmayev and Rasputin for treatment. On the evening of 16 December 1916, Protopopov urged Rasputin not to visit Felix Yusupov

Prince Felix Felixovich Yusupov, Count Sumarokov-Elston (russian: Князь Фе́ликс Фе́ликсович Юсу́пов, Граф Сумаро́ков-Эльстон, Knyaz' Féliks Féliksovich Yusúpov, Graf Sumarókov-El'ston; – ...

that night. Rasputin however disregarded this advice and was murdered at the Yusupov Palace in St. Petersburg a few hours later. It is alleged that Protopopov subsequently sought advice from the dead Rasputin at seances.

Revolution and death

On February 22, the workers of most of the big factories were on strike. OnInternational Women's Day

International Women's Day (IWD) is a global holiday celebrated annually on March 8 as a focal point in the women's rights movement, bringing attention to issues such as gender equality, reproductive rights, and violence and abuse against wom ...

, working women came out in the streets to demonstrate against starvation, war, and tsardom. On 25 February 1917, during a session of the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

gathered at Golitsyn's apartment, Pokrovsky proposed the resignation of the whole government. Belyaev suggested to remove Protopopov from his post, as he saw in him the main cause of unrest. The next day, Protopopov and Nikolay Iudovich Ivanov

Nikolai Iudovich Ivanov (russian: Никола́й Иу́дович Ива́нов, tr. ; 1851 – 27 January 1919) was a Russian artillery general in the Imperial Russian Army.

Family

Ivanov's family origin was debatable, some sources say ...

, the Commander of the Petrogradsky Military District, tried to suppress the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

. However, Protopopov ignored warnings from the Tsar's secret police, the Okhrana

The Department for Protecting the Public Security and Order (russian: Отделение по охранению общественной безопасности и порядка), usually called Guard Department ( rus, Охранное отд ...

, that the ill-disciplined and poorly trained troops of the Petrograd garrison were unreliable. The reservist

A reservist is a person who is a member of a military reserve force. They are otherwise civilians, and in peacetime have careers outside the military. Reservists usually go for training on an annual basis to refresh their skills. This person is ...

battalions of four regiments of the Imperial Guard then mutinied

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members ...

and joined the revolutionaries. Pokrovsky reported about his negotiations with the Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic. The alliance is led by the Dominican Liberation Party

The Dominican Liberation Party ( Spanish: Partido de la Liberación Dominicana, referred to here by its Spanis ...

led by Vasili Maklakov at the session of the Council of Ministers in the Mariinsky Palace

Mariinsky Palace (), also known as Marie Palace, was the last neoclassical Imperial residence to be constructed in Saint Petersburg. It was built between 1839 and 1844, designed by the court architect Andrei Stackenschneider. It houses the ci ...

, who spoke for the resignation of the government, but Protopopov refused to give up. Not long after his apartment and office were sacked by demonstrators, and Protopopov took refuge at the Mariinsky Palace. According to M. Nelipa: "On February 28, Protopopov freely walked into the Tauride Palace

Tauride Palace (russian: Таврический дворец, translit=Tavrichesky dvorets) is one of the largest and most historically important palaces in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Construction and early use

Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride ...

at 11.00 p.m. and handed himself in." Protopopov was taken to the main hall, where the former cabinet ministers were surrounded by soldiers with fixed bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustr ...

s. The new Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

under Georgy Lvov

Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov (7/8 March 1925) was a Russian aristocrat and statesman who served as the first prime minister of republican Russia from 15 March to 20 July 1917. During this time he served as Russia's ''de facto'' head of stat ...

requested him to retire from his post as Minister of the Interior, giving him the plea of "illness" if he desired. Protopopov and Prince Golitsyn

The House of Golitsyn or Galitzine was one of the largest princely of the noble houses in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire. Among them were boyars, warlords, diplomats, generals (the Mikhailovichs), stewards, chamberlains, the richest ...

were arrested and taken to the Peter and Paul fortress

The Peter and Paul Fortress is the original citadel of St. Petersburg, Russia, founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and built to Domenico Trezzini's designs from 1706 to 1740 as a star fortress. Between the first half of the 1700s and early 1920s i ...

that night.

In prison, Protopopov prepared detailed affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a statemen ...

s concerning his period in office, but he was soon taken to a military hospital

A military hospital is a hospital owned and operated by a military. They are often reserved for the use of military personnel and their dependents, but in some countries are made available to civilians as well. They may or may not be located on a ...

suffering from hallucinations

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus that has the qualities of a real perception. Hallucinations are vivid, substantial, and are perceived to be located in external objective space. Hallucination is a combinatio ...

. After the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in November 1917 and the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, Protopopov was transferred to Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

and imprisoned in Taganka Prison Taganka Prison (Russian: Таганская тюрьма) was built in Moscow in 1804 by Alexander I, emperor of Russia.Katrina Marie"Taganka: The Haunts of Intelligentsia and Blue-Collar Grit"''Passport Moscow''. Retrieved December 5, 2011 It gaine ...

. On 27 October 1918, Protopopov was executed by the Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə), abbreviated ...

, with his execution order implying his mental state as healthy./ref>

References

External links

* V.I. GurkoFeatures And Figures Of The Past. Government And Opinion In The Reign Of Nicholas II.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Protopopov, Alexander 1866 births 1918 deaths Octobrists Marshals of nobility Members of the 3rd State Duma of the Russian Empire Victims of Red Terror in Soviet Russia People from Ulyanovsk People from Ulyanovsk Oblast Russian nobility Members of the 4th State Duma of the Russian Empire Executed Russian people